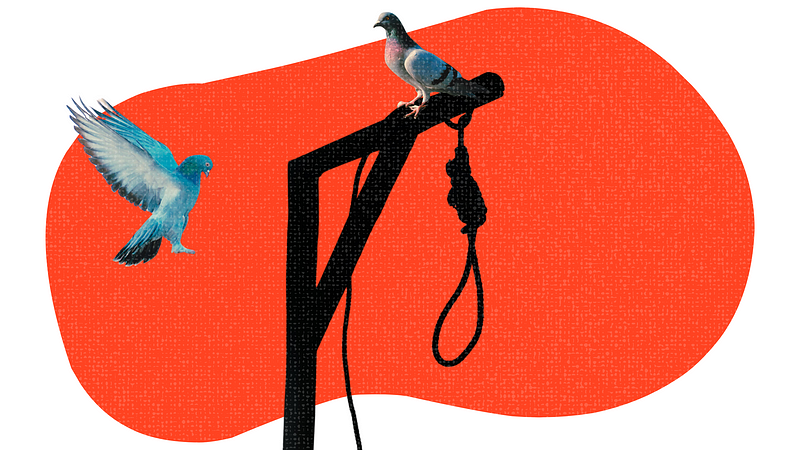

Inside an Execution Chamber: A Canadian’s Warning on the Death Penalty Debate

How new polls, political rhetoric, and lived experience clash over capital punishment

I have stood inside an execution chamber and held a man as the State of Texas killed him.

I doubt any other Canadian alive can say that, and I wouldn’t wish it on anyone.

Last June, in a tiny green brick room, I sang Ramiro Gonzales to death while pentobarbital coursed through his veins. It was one of the most devastating experiences of my life.

So when I read in a recent poll from Research Co. that more than half of Canadians (53%) are willing to reinstate the death penalty, I can’t help but wonder: What exactly do they think they’re endorsing?

A quick, painless resolution to society’s worst problems?

Some grand moral reckoning, where the world is neatly sorted into good guys and bad guys?

Have they thought about what it would mean to strap a person down and watch them die in our name?

Ontario’s Premier apparently hasn’t. At a recent gala dinner for law enforcement in London, Ontario, Doug Ford made an alarming remark in reference to violent home invaders: “send ’em right to Sparky.”

It’s a line that might get cheers from his voter base, but these are people who’ve never witnessed the carefully choreographed theatre of state-sanctioned killing.

The Research Co. poll suggests, for many Canadians, the reasons to bring back the death penalty revolve around cost, closure, and deterrence. Some believe it will save taxpayers money. Others insist it’s the best way to honour victims and bring some sense of healing to their loved ones.

And then there are the die-hard deterrence champions, convinced that fear of lethal injection will make would-be murderers see the light. If only life — or death — worked like that.

Myths vs. Reality

In truth, capital cases cost far more than imprisonment for life — and that’s not just moral conjecture. Endless appeals, specialized facilities, and solitary cells add up quickly. So if you hoped the death penalty might spare your tax dollars, think again.

According to the Research Co. poll, cost was a key motivation for many Canadians who support capital punishment — yet the real-world math says it’s anything but cheap.

Then there’s deterrence — that comforting notion that fear of lethal injection will make would-be murderers see the light. If that worked, murder rates in states with the death penalty would be practically nonexistent.

Instead, American data shows no link between executions and lower violent crime. If anything, murder rates in states that practice capital punishment are higher.

People who commit violent homicides simply aren’t pausing for a cost–benefit analysis of lethal injection vs. life in prison.

Some argue executions are needed because some people are just too dangerous to be kept alive. But by the time someone’s actually executed, they’ve spent years — often decades — behind bars. Some have found religion or tried to make amends, others remain unchanged, but nearly all are no longer a threat.

The net effect on public safety is almost zero, aside from all the money and moral contortions states pour into the process—funds that could be better spent on grassroots community safety initiatives.

In the end, we’d be left with a system that’s more expensive, fails to deter crime, and kills people who pose no further threat. It’s like burning down the house to catch a single mouse — dramatic, ruinous, and wholly unnecessary.

Death by Bureaucracy

Yet the numbers don’t tell the whole story. For every execution, there are a host of ordinary professionals forced to carry out the deadly procedure. It’s easy to forget that an execution doesn’t just happen on paper. There are people who must prep the needles, tie the rope, or flip the switch. It doesn’t matter who you are or what you think about the person being executed—killing a human being is not easy.

On execution day, I found myself walking with the warden through the prison’s garden, commiserating over the intensity of the Texas heat. Except for the fact that she and her people were preparing to poison my friend to death, she was quite lovely.

While I had expected to encounter officers who were cold and sadistic, my experience was that the guards were often staff with limited employment options, families to feed, and who had been given a truly awful job to do. “This day is hard on everybody,” the warden said.

“Some bodies more than others,” I thought.

But I believe her. I don’t believe Ramiro’s execution was easy for the staff. I also don’t mean to imply the folks at the prison are against the death penalty, or that they believed Ramiro deserved to live.

But I’ve spoken to a lot of killers over the years. You don’t look somebody in the eye, take away their life, and somehow make it out of that process whole.

Although I was entirely opposed to what was happening, officially, I was present as a volunteer of the state. The chaplain/spiritual advisor’s role in the chamber has been an integral part of the execution process since lethal injection was introduced in the early 1980s.

The moral injury of being present for an execution is real thing and my heart continues to struggle with it every day.

Supporting the death penalty means we’re asking ordinary people — guards, medics, chaplains, wardens — to perform our killing for us. It’s a collective responsibility that is delegated away.

I don’t know about you, but that’s not something I’m okay with.

Canada’s Hands Are Tied — And That’s a Good Thing

Even if Canada woke up tomorrow and decided, “Yes, let’s embrace a morally dubious, astronomically expensive, and wholly ineffective punishment,” we’ve got a major obstacle: we can’t legally do it.

Years ago, Canada signed on to the Second Optional Protocol to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, which is official legalese for “We renounce capital punishment, period.” And there’s no legal way of backing out of that protocol.

Article 1

No one within the jurisdiction of a State Party to the present Protocol shall be executed.

Each State Party shall take all necessary measures to abolish the death penalty within its jurisdiction.

Then there’s the Supreme Court’s 2001 ruling: we won’t carry out an execution ourselves, and we won’t send anyone to another jurisdiction to be executed, either. Our Charter of Rights and Freedoms has effectively slammed that door shut.

The last time Parliament voted on the death penalty was 1987. The motion failed (148 to 127), and no government since has seriously tried to revive it.

Given the tough-on-crime gusto coming from the Conservative Party, some folks are whispering that a Poilievre government might attempt to resurrect capital punishment in Canada. But here’s the rub: unless the Conservatives are prepared to shred binding international agreements like yesterday’s newspaper and whip out the notwithstanding clause for an issue this incendiary — plus blow hundreds of millions trying to establish a whole new judicial system of death — it’s not going to happen.

It might make for bold headlines, but the actual logistics are more complicated. For all that noise, reanimating the death penalty in Canada remains firmly off the table.

This is part of why Ford’s words about bringing back capital punishment anger me so much. Fear is a powerful political tool. Ford knows that when people feel unsafe, they look for simple solutions to complex problems. More prisons. Harsher sentences. The death penalty.

But what Ford and others like him won’t acknowledge is that the very people most affected by violent crime — low-income communities, racialized communities, Indigenous communities — are also those most at risk of wrongful convictions and unjust punishments.

And if we think wrongful convictions don’t happen in Canada, we’re fooling ourselves. Steven Truscott, David Milgaard, Guy Paul Morin — all men convicted of murder. All men later exonerated. Had these men been sentenced to die*, they might not have lived to see justice because the system is not infallible. And when you introduce a punishment that cannot be undone, the risk of executing an innocent person becomes all but a certainty.

*At fourteen(!), Steven Truscott had originally been sentenced to death by hanging. He was reprieved by the federal cabinet and served 10 years before being released on parole in 1969. DNA evidence exonerated him in 2007.

Canada at a Crossroads: American Influence or European Reform?

Still, we’ve been flirting with American-style rhetoric for ages. It’s easy to adopt the catchphrases of our southern neighbour — “throw away the key,” “lock ’em up,” and now “send ’em to Sparky.”

Meanwhile, The European Union has abandoned the death penalty altogether. Many of those countries focus on rehabilitation — restoring offenders to society where possible, investing in prevention, and maintaining generally lower crime rates than either the United States or Canada.

So which route does Canada choose? Do we copy American political scripts, letting fear shape our policies? Or do we invest in understanding why crimes happen, supporting victims, and tackling root causes—instead of imagining that an execution somehow solves it all?

If we’re not careful, we’ll keep singing the same old tunes: more punishment, more prisons, more expense — yet no real dent in crime. We might feel righteous, but that doesn’t mean we’re safer. The question is whether we have the humility and courage to try a different path — one that might actually heal rather than simply punish.

I know I haven’t said anything particularly groundbreaking here. The statistics surrounding the death penalty have been widely known for anybody with ears to hear for years.

And yet, here we are, with more than half of Canadians apparently thinking, “Hey, maybe the death penalty isn’t so bad after all.”

Capital punishment isn’t a magic wand. It won’t bring closure, it won’t save money, and it won’t deter future crimes. If we really want to keep our communities safe, maybe we should focus on restorative justice, supporting victims, and tackling the core causes of violence.

Because, in the end, once you stand in an execution chamber, you realize — there is no justice in this. 🦢