Lord, have mercy.

How many times had Bartimaeus asked for mercy before Jesus answered his call? Ramiro Gonzales asked for mercy too—for himself, for his people, for those who hated him.

Lord, have mercy…

In Jericho, dust clings to the feet of the passing crowd.

Bartimaeus, sightless, sits at the edges,

where silence and cries are often swallowed,

lost in the noise of busyness, brushed aside.

“Jesus, Son of David, have mercy on me!”

It’s a cry sharp as desert thorns,

insistent and persistent as breath.

Who is this voice, this broken song at the roadside,

rising against the tide of a crowd telling him to hush…hush…hush…?

Isn’t that how it is?

The world teaches us where mercy belongs,

who deserves it, who is worthy to receive it.

But Bartimaeus knows what desperation strips away—

that all he has left to ask for is mercy.

Mercy—the word we use when justice feels too small.

Mercy—the gift we give when punishment loses its point.

Mercy—the crack in the stone heart, letting light seep through.

And Jesus, who hears what others dismiss, stops.

“What do you want me to do for you?”

Like a healer listening not to the illness, but to the humanity,

of the one before him:

asking Bartimaeus to name the need himself.

To ask for mercy is a brave thing.

For Bartimaeus, it means daring to believe

that even he, left on society’s edge, is seen—

fully, deeply, worthily seen.

It means believing that healing can be his,

that his blindness doesn’t define his belonging.

Mercy.

He could be asking for any of us…

Lord, have mercy…

listen to this sermon in podcast format

My friend was killed his summer.

He was killed as those who hated him,

those he'd hurt,

named the occasion as joyous.

But before this,

despite everything he had done,

all the harm he’d wrought in his broken years,

when violence and despair were his only language,

Thousands of us lifted our voices,

pleading mercy on Ramiro’s behalf.

In letters, in clemency petitions,

we wrote and rewrote the reasons he should live,

as if a life should ever need defending.

But Texas, whose veins run red with retribution,

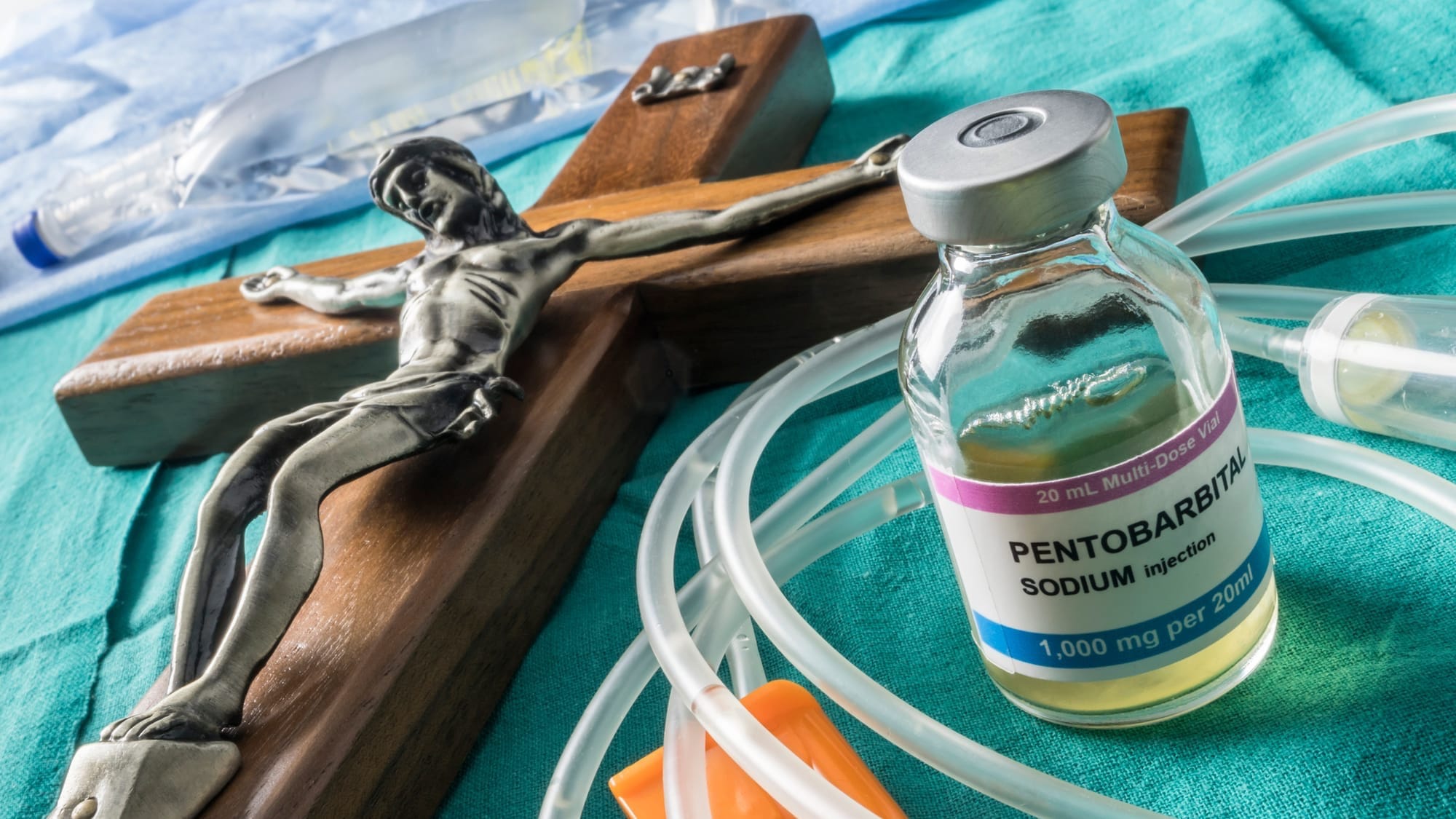

answered only with silence and poison.

In the end, they took him anyway.

Lord, have mercy…

As a child, Ramiro walked through shadows,

a world edged in violence,

where love was a language no one remembered,

and loneliness settled like dust on his skin.

Shaped by bruises and silences,

Ramiro was a lost boy, seeking light in a place,

where generations had been stripped of the ability to dream,

of mercy, of healing,

that life could be anything more.

Then, as a prisoner, he lived,

bearing the weight of all he had done.

Yet even there, in the silence of the cells,

he found pieces of himself again,

patching a heart shattered so young.

First learning to speak softer words,

then finding hands could be used for prayer, not pain.

Finally, ears that heard God’s call on his heart:

"There is mercy enough for all,

there is mercy enough for you.

Your faith has made you well—

rise and follow me."

And in that barren, broken place,

his quiet light began to grow,

a faith unbound by the confines of men,

leading toward a wholeness the world could not take away.

Over the years,

Ramiro’s spirit began to ascend,

unfolding in faith, hope, and love,

a fragile testament to change…

A testament that that those in suits,

and the Governor’s pocket,

did not read in their bibles.

They saw fragments of Ramiro’s past,

but not the quiet mending of his spirit.

They counted the harm he’d caused,

not the harm that had shaped him,

And with that balance, they felt justified.

You see, they needed a scapegoat to carry the burden,

of a wounded society’s unacknowledged shame,

for carving the very chasm where so many like Ramiro are lost.

So they marked him for death,

believing his end would cleanse their own hands.

Indifferent, as they were, to the man he had become,

to the mercy he’d found in prison walls,

to the grace that rose from the ruins,

to a boy they only cared to know,

When somebody needed to pay.

And Ramiro prayed to a God who knows what that’s all about.

Lord, have mercy…

I’d just spent two hours with Ramiro in the holding cell,

our voices rising together with the words of very old hymns,

the only songs of praise we shared:

Amazing Grace, Be Thou My Vision,

Shall We Gather at the River reverberated through the concrete and steel…

He was sad.

He was scared.

But he knew where he was going.

Ramiro’s faith held a strength I could only reach for,

and his words, though few, were only of love—

for friends, family,

for the friends and family of Bridget Townsend,

who had carried anger like a torch for two decades

begging for his death as a balm for their pain.

And as we prayed, his voice softened,

lifting up the prison staff in prayer,

those who would soon strap him down,

a prayer of mercy for those responsible for facilitating his end.

Lord, have mercy…

I knew before walking in to the execution chamber,

Ramiro cruciform on the table,

that of all of us standing there,

witnessing life stolen away,

Ramiro would be the most well.

The warden, stiff with duty’s weight,

was not well,

for there is a cost to taking life,

a toll that settles in the bones.

The witnesses, bound forever by what they saw,

were not well,

holding within them what could never been unseen:

A homicide. A trauma. A loss as profound that it will never leave.

The executioner—

how could anyone well enough

raise a hand to end a heartbeat?

And I, merely standing, praying,

was not well,

for all I could do was sing,

sing these words,

asking mercy…mercy…mercy…

for every spirit held captive in that chamber,

including my own.

Lord, have mercy on me too,

for I did nothing to stop it,

stood silent as condemnation closed its grip on life.

And yet—Ramiro, bound, still,

strangely, tragically,

was the only one well,

the only one spiritually whole,

His faith steady,

his peace rising like a prayer,

that we, the broken,

might one day understand.

His last words on this earth were of love.

As the drug began its silent course,

he turned to me and said,

"I love you, Mana."

and then he was taken.

Lord, have mercy…

Mercy? Mercy says come in.

Mercy opens what we try to close;

Mercy refuses the final word of shame.

Jesus’ question echoes in this space:

“What do you want me to do for you?”

How many times, I wonder, had Bartimaeus

raised his voice for mercy?

Cried out in the darkness for help,

for love, for the touch that heals?

How many times had he insisted, unseen,

that he too was worth noticing,

—his voice choking in the dust—

before Jesus walked by?

Do we dare hope that mercy might be for everyone?

For those without home, food, friends, care?

For those whose bodies bear the mark of both personal and systemic failings?

That it stretches to the condemned and the convict?

That mercy is, perhaps, our truest glimpse of God?

Do we believe mercy might even be for us?

In Bartimaeus’ plea,

in Jesus’ reply,

we glimpse the heart of the divine—

a God whose mercy cannot be stilled,

who hears through the crowd’s indifference,

who stops, who sees, who calls, “Come near.”

And today, as Ramrio prayed,

as I prayed:

Lord, have mercy.

Whom might we hold in mercy’s reach?

And will we be bold enough to cry out?

Will those who can grant both life and death at the stroke of a pen join in,

“Jesus, Son of David, have mercy on us all“?

Loving as Ramiro loved,

insisting as Bartimaeus persisted,

we pray,

for a world aching to be healed,

for a justice shaped in God and mercy’s name.

Yes, Lord, have mercy.

Amen.