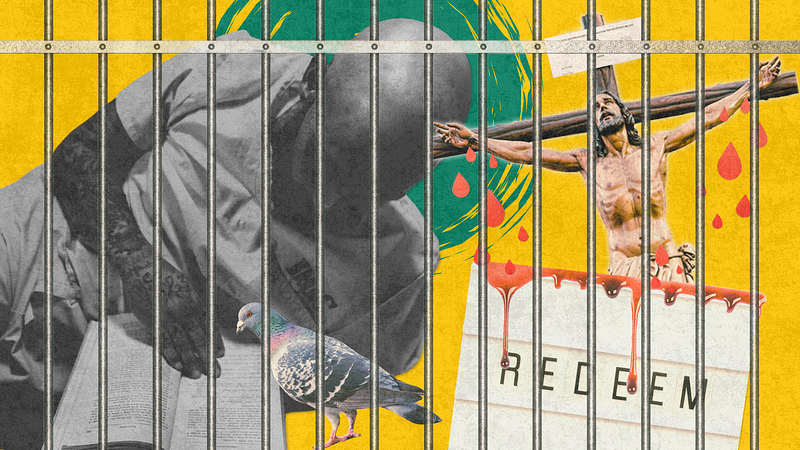

When Justice Demands Blood: The Theology That Built America’s Prisons

How penal substitutionary atonement shaped mass incarceration and the death penalty

I sat across from a man on death row as he looked me dead in the eyes and told me that Jesus had paid his debt.

And when he said it, he meant it. It wasn’t some soft-focus Sunday School lesson, not some pleasant little theological metaphor you might tuck into your pocket and pull out when the world feels mean. No, he had done something terrible, something that could never be undone. There were no take-backs, no do-overs, no amount of sorry that could stitch his victims’ lives back together. He knew that.

And yet, here he was, sitting in a fluorescent-lit cage, telling me that Jesus had stepped in, picked up the tab, and paid everything in full.

And I wanted to argue. I wanted to tell him that I find it hard to believe in a God who creates a world where everyone is so irredeemable that someone needed to die just to make things right. That he is not loved because of some cosmic transaction, not because Jesus had to take his place like some divine scapegoat, but because he is beloved. That God’s mercy extends to all and without a price tag. That God knows the deepest, most hidden parts of who he is, the parts that even he cannot bear to face, and loves him still.

But then I saw the way he held onto that belief — not with arrogance, not with entitlement, but with the desperation of a drowning man clutching a life preserver. He needed it to be true.

That’s the thing about theology that I sometimes need reminding of: It is not some theoretical abstraction, some polite academic debate happening in a classroom full of well-meaning seminarians.

It is what people breathe when they would otherwise perish.

The Origins of Penal Substitution: A Blood-Soaked Ledger

The idea that Jesus died as a substitute, taking the punishment that rightly belonged to humanity, is not the only way Christians have understood the cross. But it is the dominant way in many circles, particularly in America—a country who loves nothing if not a system of debts and payments, crime and punishment.

The early church, for its first thousand years or so, leaned more into Christus Victor — the idea that Jesus triumphed over sin and death, that the cross was a cosmic jailbreak rather than a transaction.

But then along came Anselm of Canterbury in the 11th century, and like any good medieval thinker, he viewed sin as an offence against divine honour, something that required satisfaction.

And from there, under John Calvin and the Reformers, it got even sharper, more forensic: God is just, justice demands payment, and Jesus, mercifully, pulled out the chequebook.

It is a neat system, clean and orderly. A divine balance sheet where all the accounts settle in the end.

It makes sense, I suppose, if you’ve grown up in a world that tells you everything — love, forgiveness, even salvation — must be bought and paid for.

And that, of course, is exactly the world we live in.

Penal Substitution in the American Justice System: The Cross as a Courtroom

If you ever want to understand how deeply theology seeps into culture, look at how a country builds its prisons.

In the U.S., where evangelical Christianity has had an outsized influence over public policy, penal substitution isn’t just a doctrine —it has shaped an entire legal system.

The logic of penal substitution is the logic of retributive justice: crime demands punishment, and justice is only served when a price is paid. No surprise, then, that the U.S. locks up more people per capita than any other country — not because Americans are especially wicked, but because the U.S. believes, with the fervour of a revival preacher, in punishment.

It doesn’t just think justice should be served; America wants it plated up, scalding hot, with a side of suffering.

The logic is baked in deep: Jesus had to bleed to balance the spiritual books, so criminals must pay in flesh and years to make things right. Never mind if it actually rehabilitates anyone, never mind if it heals anything. The pain is the point.

So, prisons are built instead of schools. Policies are crafted that focus on retribution instead of rehabilitation. People are kept locked away long after their risk to society has passed because justice, we are told, means that someone must pay.

And it is no coincidence that the death penalty remains legal in states where penal substitution is most deeply ingrained. The logic is the same: sin equals death, and someone has to die.

The Inmates Who Believe It — And Why It Saves Them

But here is where things get complicated. Because as much as I wrestle with penal substitution — and believe me, I do — I can’t ignore the fact that for some of the men I’ve met behind prison walls, it’s the thing that keeps them getting out of bed in the morning.

Imagine carrying the unbearable weight of the worst thing you’ve ever done, knowing that no amount of sorrow, no act of atonement, not even a lifetime spent on your knees could scrub it away. And then someone comes along and tells you: You don’t have to. That somehow, impossibly, grace has already covered it.

Wouldn’t you cling to that, too?

Some on death row turn to anger, refusing to let anyone near the broken place inside them. Some go mad, lost in the voices in their heads and the ghosts of their victims.

And then there are the ones who find God.

For them, penal substitution is not about courtroom justice. It is about mercy*.

And so I sit across from these men, and I listen, and I try to hold all of it — the grace and the violence, the justice and the mercy, the terrible things they have done and the inexplicable fact that they are still, somehow, beloved by God.

Just as we all are.

The Consequences of Harmful Theology

I struggle with penal substitution because I have seen what it does to people outside of prison, how it shapes a culture that equates justice with suffering and therefore resists mercy because it feels too soft. I have seen how it fuels mass incarceration, how it undergirds a system that locks people away and throws away the key.

But I have also seen what it does inside prison, how it gives men the ability to keep waking up in a place designed to erase them. And I do not know what to do with that contradiction.

There are other ways to understand atonement, other ways to see the cross — not as divine child abuse or as a blood price to satisfy an angry God, but as an act of holy love, a rejection of the powers of sin and death, and a call to reconciliation rather than retribution.

I wonder what it would look like if the American justice system were built on that kind of theology instead.

But for now, I sit across from these men, and I do not argue. I simply pray and let them tell me about the Jesus who took their place. Because in a world where grace is often in short supply, I will not begrudge anyone the mercy they have found, even if it is not the one I would have chosen for them.

If penal substitution tells us anything, it tells us that something had to change. Maybe that is the part we should be paying attention to. Not the demand for blood, but the insistence that mercy is possible. Even in the darkest, most hopeless of places.

Even for the worst within all of us. 🦢

*There is another discussion to be had here — one about how penal substitutionary atonement is the theology these men subscribe to because it is the pastors who believe in it that show up in the visiting rooms. In my experience, I am far more likely to meet evangelical pastors in those spaces than I am pastors from my own mainline Protestant tradition. These are the ones who come, who listen, who sit with men who have been condemned by the world and tell them that grace is still on offer. And that, perhaps, is another conversation for another time.

Hi! 👋🏼 I’m Rev. Bri-anne. You can also find me on BlueSky🦋, serving the fine folks of East End United Regional Ministry in Toronto, or leading the Resistance Church digital community.

Join my website and mailing list 👉🏼 here👈🏼

You can support Resistance Church and keep me going with a ☕️ here (thank you) .